For years, I’ve been referring to my own research and observations on mobile device use, which indicate that people grasp their mobile phones in many ways—not always one handed. But some of my data was getting very old, so included a lot of information about hardware input methods using keyboard- and keypad-driven devices that accommodate the limited reach of fingers or thumbs. These old mobile phones differ greatly from the touchscreen devices that many are now using.

Modern Mobile Phones Are Different

Everything changes with touchscreens. On today’s smartphones, almost the entire front surface is a screen. Users need to be able to see the whole screen, and may also need to touch any part of it to provide input. Since my old data was mostly from observations of users in the lab—using keyboard-centric devices in too many cases—I needed to do some new research on current devices. My data needed to be more unimpeachable, both in terms of its scale and the testing environment of my research.

So, I’ve carried out a fresh study of the way people naturally hold and interact with their mobile devices. For two months, ending on January 8, 2013, I—and a few other researchers—made 1,333 observations of people using mobile devices on the street, in airports, at bus stops, in cafes, on trains and busses—wherever we might see them. Of these people, 780 were touching the screen to scroll or to type, tap, or use other gestures to enter data. The rest were just listening to, looking at, or talking on their mobile devices.

What My Data Does Not Tell You

Before I get too far, I want to emphasize what the data from this study is not. I did not record what individuals were doing because that would have been too intrusive. Similarly, there is no demographic data about the users, and I did not try to identify their devices.

Most important, there is no count of the total number of people that we encountered. Please do not take the total number of our observations and surmise that n% of people are typing on their phone at any one moment. While we can assume that a huge percentage of all people have a mobile device, many of these devices were not visible and people weren’t interacting with them during our observations, so we could not capture this data.

Since we made our observations in public, we encountered very few tablets, so these are not part of the data set. The largest device that we captured in the data set was the Samsung Galaxy Note 2.

What We Do Know

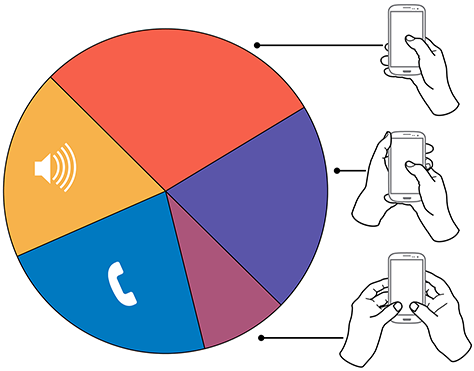

In over 40% of our observations, a user was interacting with a mobile phone without inputting any data via key or screen. Figure 1 provides a visual breakdown of the data from our observations.

To see the complete data set:

Voice calls occupied 22% of the users, while 18.9% were engaged in passive activities—most listening to audio and some watching a video. We considered interactions to be voice calls only if users were holding their phone to their ear, so we undoubtedly counted some calls as apparent passive use.

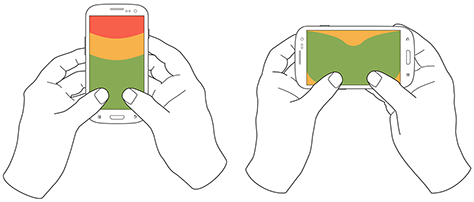

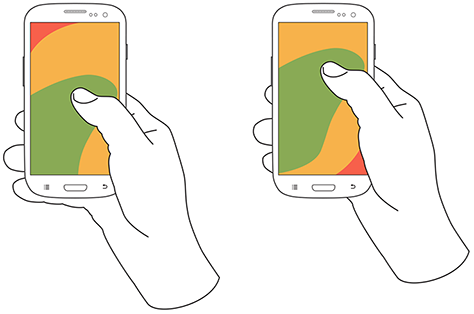

The users who we observed touching their phone’s screens or buttons held their phones in three basic ways:

- one handed—49%

- cradled—36%

- two handed—15%

While most of the people that we observed touching their screen used one hand, very large numbers also used other methods. Even the least-used case, two-handed use, is large enough that you should consider it during design.

In the following sections, I’ll describe and show a diagram of each of these methods of holding a mobile phone, along with providing some more detailed data and general observations about why I believe people hold a mobile phone in a particular way.

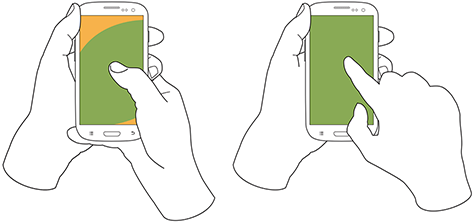

In Figures 2–4, the diagrams that appear on the mobile phones’ screens are approximate reach charts, in which the colors indicate what areas a user can reach with the finger or thumb to interact with the screen. Green indicates the area a user can reach easily; yellow, an area that requires a stretch; and red, an area that requires users to shift the way in which they’re holding a device. Of course, these areas are only approximate and vary for different individuals, as well as according to the specific way in which a user is holding a phone and the phone’s size.

Users Switch How They Hold a Mobile Phone

Before I get to the details, I want to point out one more limitation of the data-gathering method that we used. The way in which users hold their phone is not a static state. Users change the way they’re holding their phone very often—sometimes every few seconds. Users’ changing the way they held their phone seemed to relate to their switching tasks. While I couldn’t always tell exactly what users were doing when they shifted the way they were holding their phone, I sometimes could look over their shoulder or see the types of gestures they were performing. Tapping, scrolling, and typing behaviors look very different from one another, so were easy to differentiate.

I have repeatedly observed cases such as individuals casually scrolling with one hand, then using their other hand to get additional reach, then switching to two-handed use to type, switching back to cradling the phone with two hands—just by not using their left hand to type anymore—tapping a few more keys, then going back to one-handed use and scrolling. Similar interactions are common.

One-Handed Use

While I originally expected holding and using a mobile phone with one hand to be a simple case, the 49% of users who use just one hand typically hold their phone in a variety of positions. Two of these are illustrated in Figure 2, but other positions and ways of holding a mobile phone with one hand are possible. Left-handers do the opposite.

Note—The thumb joint is higher in the image on the right. Some users seemed to position their hand by considering the reach they would need. For example, they would hold the phone so they could easily reach the top of the screen rather than the bottom.

One-handed use—with the

- right thumb on the screen—67%

- left thumb on the screen—33%

I am not sure what to make of these handedness figures. The rate of left-handedness for one-handed use doesn’t seem to correlate with the rate of left-handedness in the general population—about 10%—especially in comparison to the very different left-handed rate for cradling—21%. Other needs such as using the dominant hand—or, more specifically, the right hand—for other tasks may drive handedness. [4]

One-handed use seems to be highly correlated with users’ simultaneously performing other tasks. Many of those using one hand to hold their phone were carrying out other tasks such as carrying bags, steadying themselves when in transit, climbing stairs, opening doors, holding babies, and so on.